Unpacking the Truth: Pistol vs. Revolver Reliability and Mechanics for Every Handgun Enthusiast

The debate has been going on as long as the semi-automatic pistols and their ancient revolver equivalents have existed. Go to any gun store, visit any Internet discussion group, or even share a family dinner table (as some of us are all too familiar with!), and you will hear a heated debate about which handgun is the best one, particularly when your own life is at stake. The discussion is usually full of false suppositions, subjective prejudices, and simple fake news, which creates an image that may not necessarily be the truth about how these guns work when it really counts.

We will strip the myths and speculations off to-day to come to the root of the problem: What is the actual difference between a pistol and a revolver, and how do their complex mechanisms really bear upon their dependability in the profession? This is not merely about what is right, but rather knowing the engineering, the practical implications of the same and finally, a well-informed decision that may one day prove to be lifesaving. Although both platforms have their strong points and of course both can and do fail, the type of failure and at what point is a monumental difference.

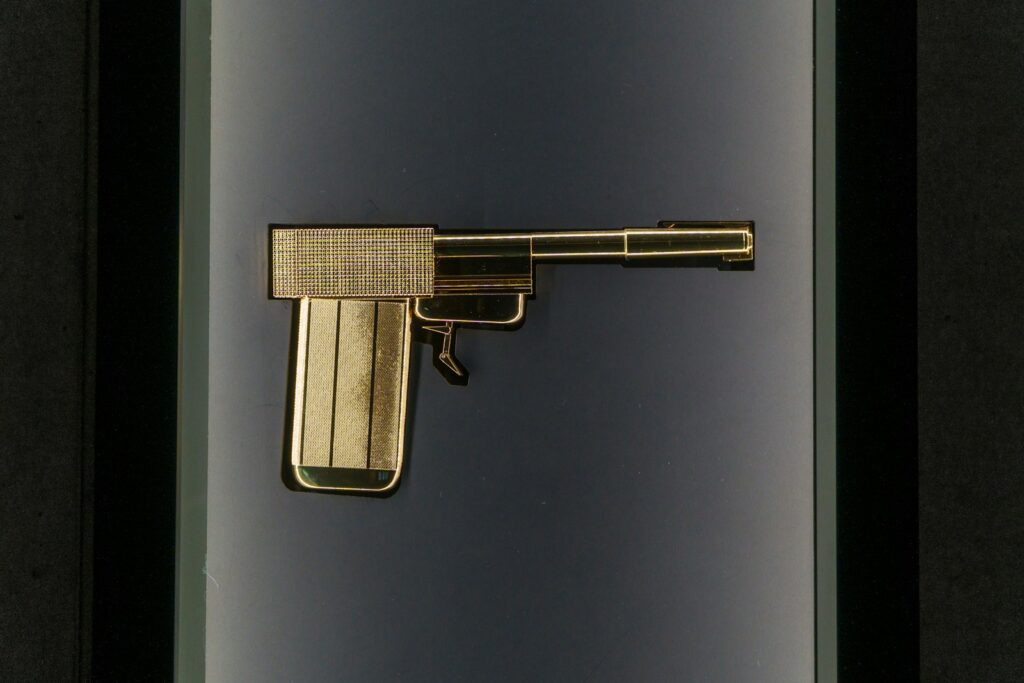

Before we start our in-depth analysis, it is important to have a general idea of what we are actually comparing. When the word pistol is mentioned in everyday speech, the image that comes to mind is that of a modern, semi-automatic, magazine-fed handgun, and that is what we are going to be discussing. In this case, a pistol is any firearm in which the chamber is a part of the barrel, and it is fired by a semi-automatic mechanism. This implies that as the trigger is pulled, not only does a round get fired, but the cycle automatically repeats, and the spent casing is thrown off and another round loaded out of a detachable magazine.

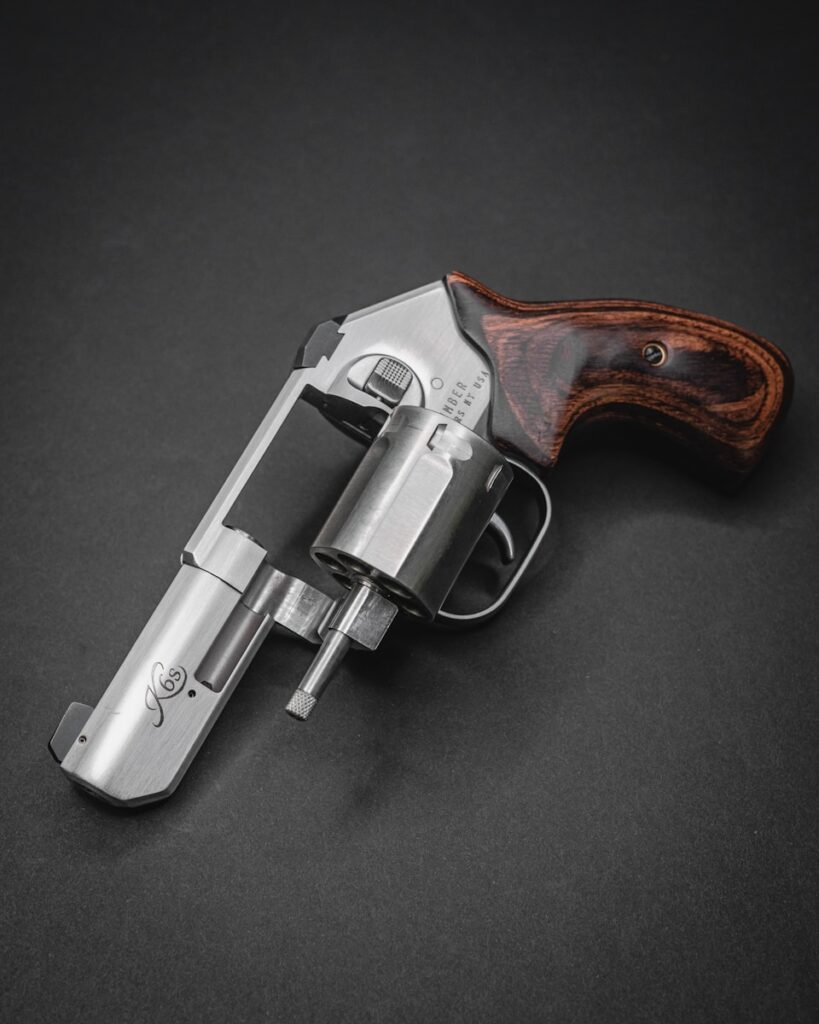

On the other hand, a revolver is a handgun in which the chamber is not a part of the barrel. The cartridges are instead contained in a rotating cylinder. With every triggering, this cylinder turns to position a new round with the barrel, and it is ready to shoot. Although revolvers may be either single or double action, in the case of self-defense and concealed carry, we will mainly focus on modern day, double-action revolvers, in which the trigger can both cock and release the hammer. These are the basic differences in design, which form the foundation on which all other differences in reliability, ease of use and practical application are based.

Knowledge on Failure Myths and Realities

Next we shall deal with one of the most enduring myths; that revolvers do not jam. As much as it is true that you will not feel like you have a stovepipe or failure to feed with a revolver as you would with a semi-auto, it would be a dangerous oversimplification to say that they never fail. The mechanical simplicity of a revolver is in fact a considerable virtue and many tend to think that it cannot be affected by any malfunctions. This notion is usually based on the reality that it does not depend on a complicated slide cycling system or a feed ramp which can become clogged, and thus it is naturally immune to ammunition feeding problems.

But there are certain caveats to this mythical dependability. Revolvers may jam, and when they jam it is usually a worse and less easily corrected issue than most semi-auto failures. The usual culprits are dirt and grime, a mechanism that is out of time, or debris that somehow gets under the ejector star, and does not allow the cylinder to rotate freely. Once this kind of failure has been experienced, it is not a tap-rack-slap solution. The gun is essentially out of action instead unless you possess the tools and the knowledge to clear it on a bench. Although these disastrous failures are not common, when they occur, then it is all over with that specific engagement.

Conversely, semi-automatic pistols are commonly viewed as being less reliable in nature. Having a bad round, a loose grip (also known as a limp wrist) or a magazine not properly seated can be a normal occurrence with the owners of a pistol and can cause a malfunction. This view of increased failure rates tends to dwarf the progress of the modern pistol design. Modern duty-sized handguns, including the Glock 17 or the SIG P320, can easily cycle full magazines without any problems, even in less-than-perfect environments.

The important difference here is not whether they fail but the manner in which they fail. A semi-automatic pistol can be cleared in a few seconds when it malfunctions because of the usual causes such as a feed error or failure to eject. A sharp rack and a slap frequently put you back in the battle, and you have the essential time when every second matters. A pistol, unlike a revolver, usually provides the user with a chance to quickly troubleshoot the issue and fix it, continuing the interaction without having to spend much time. This quick ability to clear malfunctions can become a determining element in a dynamic, high-stress situation.

Ease of Operation and Learning Curve

The mechanical design is also very significant in the initial learning curve and complexity of operation by the user. Revolvers are frequently praised as being simple. Normally, there are only two main controls of a revolver: the trigger and the cylinder release. External safeties to disengage (on most modern double-action models) are absent, slide locks are absent, and magazine releases in the semi-automatic sense do not exist. The simple process of aiming the gun at the target and drawing the trigger until it clicks, bangs, makes revolvers extremely simple to learn and operate, providing an instant feeling of accessibility.

But this ease of use is usually a deception to a more difficult task of learning to use the revolver properly, particularly in the case of precise shooting when under pressure. The heavy, generally long, double action trigger pull, though a safety measure in itself, takes much practice to master to achieve consistency. Although it takes only a few minutes to learn the fundamentals of operating a revolver, it takes a lot of dedication and training to become proficient, especially in the ability to shoot and hit a target with a revolver in a short period of time.

In comparison, semi-automatic pistols seem to have a more complicated set of controls. In addition to the trigger, a standard semi-auto will have a slide lock, a magazine release button and perhaps an external safety or a decocker. To learn to use these many controls with ease and instinct in time of need, demands more preliminary teaching and practice than a revolver. The process of loading, charging, and unloading a semi-automatic pistol has more steps and may be confusing at first to a person who is new to guns.

However, when these controls are mastered and trained, the semi-automatic pistol can be found to be easier to shoot straight by the average shooter, especially those who have not spent a lot of time in practicing. The relatively reduced and lighter trigger pull of most modern striker-fired pistols makes accurate placement of a shot less physically challenging than negotiating a heavy double-action revolver trigger. This is an ergonomic benefit, and the grip surfaces are usually larger to be easier to hold, which makes learning easier and acquiring proficiency faster to many.

Maintenance, Neglect and Ammunition Tolerance

In addition to the short-term operational aspects, the differences in the designs also indicate varying tolerances to neglect and ammunition quality variability. And the truth is, not all people are fastidious gun owners that clean their firearm after each trip to the range. There are guns that have spent years in a glove box or are only cleaned when they are seen to be crusty. In this case, revolvers appear unexpectedly frequently as the heroes of endurance. Having fewer springs, no slide to recycle, no feed ramp to foul, a revolver is much more lenient in occasional maintenance.

Its powerful self-contained mechanism is not so sensitive to the build-up of dirt and grime that slows moving components. Unless the ammunition is damaged and nothing has rusted solid, a revolver will tend to go bang even after a long period of neglect. This is why it is a great option as a backup gun, a bugout bag gun, or a rural carry option where regular and in-depth cleaning may not be a priority or even possible. It is a bitter pill that some pistol lovers have to swallow, but in the long run, in terms of storage and low maintenance, a revolver does not mind how lazy you are.

Pistols, in their turn, require a little more care to remain useful. They have more complex operating systems, where slides reciprocate and other springs are in action and hence more prone to performance deterioration due to thickening lubricants or excessive carbon deposits. Although the modern pistols are very tough, they work best in a moderate degree of cleanliness and lubrication. An unattended pistol may perform slowly or have more malfunctions.

As far as ammunition quirks are concerned, pistols are usually more forgiving. The vast majority of shooters have at one time, or another loaded whatever is cheapest or experimented with dubious reloads. This can easily get one into trouble with revolvers. The cylinder may become bound up by high primers, slightly swollen brass or soft lead bullets that shed material and bring the whole firearm to a standstill. The tolerances that are necessary to ensure that the cylinder turns and the chambers fit together perfectly imply that a small ammunition anomaly can cause a hard failure.

Sensitivity to Ammunition and Tolerance in the Real World

On the other hand, more recent semi-automatic pistols, especially those with striker-firing, are more ammunition-tolerant. Although dubious reloads or brand switching may result in a grimier gun or a feed problem every now and then, it is much less likely to result in a full mechanical lockup that would render the gun unusable. A pistol may be a little more rugged, or have a higher percentage of clearable failures, but its structure permits it to continue to run over a broader spectrum of ammunition defects. This natural versatility of ammunition type can be a great benefit to the economically minded or where a diverse supply is available.

Simply put, there is usually a basic trade-off between the first decision on whether to use a pistol or a revolver. Do you value the rough, nearly stoic simplicity of a revolver, which, although subject to infrequent but disastrous malfunctions, can be neglected and provide a simple user interface? Or are you more inclined to the more mechanically complicated semi-automatic pistol, which, though it may have higher rates of clearable failures, is more flexible in the use of ammunition and has a faster recovery time, but requires more regular maintenance and a somewhat higher initial learning curve of its controls? The solution, as we will see further, is not often black and white, but lies in the realization of these fundamental mechanical and operational disparities.

After breaking down the fundamental mechanical and operational distinctions of pistols and revolvers and busting some of the popular myths about the relative vulnerability of each to failure, it is time to get beyond the hypothetical. What are these underlying differences when you are confronted with a real-world situation? What is the actual comparison of capacity, practical maintenance factors, and performance in critical situations of modern handguns? The answer, as we shall see, is a subtle image that goes well beyond mere revolver-don’t-jam propaganda. Both platforms have their own benefits and drawbacks which become very clear when the stakes are high and require a more in-depth insight of anyone who takes the issue of self-defense or being a responsible gun owner seriously.

Ammunition capacity is one of the most obvious and immediate differences which affect the real-world performance. This is not a new revelation, but its importance cannot be overemphasized when it comes to reliability in a dynamic encounter. The majority of current semi-automatic pistol models have a capacity of 10 to 20 rounds in their magazines, and even the more popular micro-compact models are reaching impressive double-digit capacities. This can be compared with the average revolver which usually has a modest five or six rounds in its cylinder with larger ones occasionally having up to seven or eight. This difference in the number of rounds provides a significant margin of safety and maneuvering.

Capacity, Maintenance and Environment Problems

Consider the situation where you are faced by more than one attacker or a threat that cannot be dealt with by just a few shots. The breathing room in such a situation is priceless, and the number of rounds in the magazine of a pistol is priceless. Each shot really counts in a self-defense scenario, and additional opportunities are themselves a kind of reliability, and can provide the psychological comfort of knowing that you are sufficiently prepared. Although you may never have to empty a magazine of bullets in self-defense, the ability to do so may be a key factor. This is the basic reality as it has been observed in the larger context where capacity favors the pistol each and every time.

The reliability debate frequently goes hand in hand with the realities of maintaining and the ability of a gun to work in less-than-optimal environments. In this case the old wisdom tends to say that the revolver is king, and there is a good many things to that. Revolvers have been praised because of their capability to operate even when they are not taken care of and shrug off dirt and grime that would bring a semi-automatic to a crawl. A revolver is certainly more forgiving, should you be planning to leave your gun in a glove box and store it five years or even should you not be a regular cleaner.

The simple revolver mechanism, with fewer complex springs, no reciprocating slide to cycle, no feed ramp to foul with accumulated dirt and thickening lubricants, is just less susceptible to the influence of accumulated dirt and thickening lubricants. A revolver is usually more likely to go bang after long neglect, provided the ammunition itself has not been spoilt and nothing has rusted solid. This natural toughness also makes it a great option as a backup gun, a bugout bag firearm, or in rural carry situations where regular and comprehensive cleaning may not be an option. It is an argument that even the most ardent pistol fans tend to grudgingly admit when you need to store a gun long and do not want to maintain it, a revolver just does not mind how lazy you become.

Semi-automatic pistols, in their turn, usually require a little more careful care in order to ensure maximum reliability. They have more complex operating systems, including the fine art of the slide, multiple springs and a feeding system that is finely tuned, and thus are more prone to performance loss due to excessive carbon deposits, or lubricants that have coagulated over time. Although the current day pistols are designed to be extremely durable, they tend to perform at an average level of cleanliness and fresh lubrication. A pistol that is neglected, compared to a neglected revolver, may either run slowly, or have a much higher rate of failures.

In addition to overall maintenance, the nature of ammunition employed, and its quality also have a significant effect on real-world reliability, which also brings out another interesting difference between the two platforms. The vast majority of shooters have at one time or another fallen into the trap of using the lowest quality ammunition they could find or trying dubious reloads. This can easily get one into trouble with revolvers. The exact tolerances needed to have the cylinder free to rotate and chambers to fit perfectly imply that even minor ammunition variations can result in a hard failure.

Ammunition Problems and Stress Performance

High primers, slightly swollen brass casings or soft lead bullets that shed material can cause the cylinder to bind up halting the entire firearm. A failure of this sort caused by an ammunition load in a revolver is usually a total mechanical jam, putting the gun out of commission completely. This makes revolvers less tolerant of ammunition peculiarities, and they demand a greater level of consistency in the cartridges that they eat. It is a very important consideration in case you expect a diverse or cost-conscious supply of ammunition.

On the other hand, current semi-automatic pistols, especially heavy striker fired models, are more ammunition tolerant. Although it may result in a sloppier gun, more frequent cleaning, or a feed problem every now and then, far less likely is that it can result in a total lockup of the mechanism that makes the gun unusable. A pistol may be a bit rougher, or may have more clearable malfunctions, but its design usually permits it to continue to run with a broader variety of ammunition imperfections. Such inherent ammunition type flexibility can prove to be a major strength to the person who values economy or has access to a less-than-pristine supply chain.

The performance peculiarities of pistols and revolvers are further emphasized by critical situations, especially those that imply extreme environmental conditions. Cold weather, as an example, is a great leveler, and the weakness of both designs is revealed. As the context indicates, both designs are revealed in cold weather. Have you ever attempted to use a snub-nose revolver with a pair of heavy winter gloves on? The tough pull of the double-action trigger is even tougher, the little hammer hard to operate, and when the mechanism becomes slow with cold or grease, it can be fixed in the field easily. You have whatever that two-punch grip of heavy gloves likes.

Pistols, however, are also not able to perform well in cold weather. Thickening of lubricants may slow down the reciprocation of the slide and heavy carbon accumulation may worsen these problems. Nevertheless, one of the major differences is the possibility to train around the failures of the pistols. Through practice, a shooter can be trained to overcome a slow slide or overcome a malfunction caused by cold weather through drills. Finally, in such circumstances, the gun that performs best is the one that you can actually operate, and the design matters much less than the user proficiency.

Reload Speed and CQB Realities

The capability to reload fast and efficiently in the face of severe stress is another critical factor of real-world dependability. Every second matters in a high stakes fight and the reloading process on the two platforms is drastically different. Semi-automatic pistols have a definite advantage in this. Reloading a pistol is not very complicated: press the magazine release button, drop the used magazine, quickly insert a new one, and either press the slide release or rack the slide to load a new round. This can be done within a few seconds with practice and is therefore a very effective way of replenishing ammunition.

Reloading a revolver, however, is much finer motor, and can be greatly impaired by adrenaline and the physiological impact of stress. To reload a revolver, you usually swing out the cylinder, pop out empty shells, then drop fresh bullets into each hole one at a time. Though speed loaders or strip clips help move things along, you’ve got to line up several rounds just right and push them in using the tool’s mechanism. Since it involves many careful steps, reloading takes longer when pressure’s high making mistakes way more likely when timing really counts.

A different tricky situation involves shooting while holding the gun near your torso say, during a physical fight where you’re guarding your weapon. Instead of relying on typical semi-autos, revolvers handle this better. Without a moving slide, they don’t get hung up on fabric or skin when fired from tight spots. Certain models without exposed hammers can actually go off safely right from a coat pocket or purse, giving quicker access under rare conditions. Though most people won’t face these moments, those training for high-risk roles may find this useful.

Pistols might jam if shot while pressed against clothes or skin. Since the slide needs room to move back, touching something can stop it from working right. Even though practice helps reduce this issue, folks still need to know about it. In much the same way, how tough it is to learn at first ties into shooting straight under pressure. Though revolvers are easier to use at first, that thick double-action pull takes lots of reps to master especially when aiming fast and steady during tense moments. On the flip side, pistols usually come with snappier triggers and better grip shapes, helping most shooters nail tight groupings quicker. That speed boost? It might make all the difference when every millimeter counts.

Choosing Based on Worst-Case Scenarios

When picking between a pistol or a revolver, what really matters is how well it fits your idea of a true emergency. The truth? It’s about which gun suits your toughest situation best. Say you’re facing one critical shot at night not second tries and just need something that fires without fail; then maybe a revolver feels like the better fit. Since it doesn’t rely on clips or complex loading tricks, its straightforward design can work in your favor when everything rides on that one instant.

Still, picture facing more than one threat having to swap mags mid-chaos, or fixing a jam while soaked in dirt and rain. In those moments, today’s auto-loader gives you a real edge. More rounds up front, quicker mag changes, plus clearing snags on the fly? That’s what helps when things shift fast. It’s not only whether the thing fails it’s what goes down after it does, and how quick you bounce back. Real talk comes from practice, sweat, knowing your limits, and seeing clearly where you stand. Truth is, some revolvers break. Some pistols run forever. Learn your tool. Understand your own mind. Prep for disaster, not the perfect test range day. Moving ahead means grasping how stuff actually works – not chasing old tales.